The Massacre in My Family History

Amish among the Indians

The Hochstetler massacre takes place in 1757, but it affects me today. The story has been passed down from generation to generation. The massacre is part of my heritage, my people, and our God.

The Delaware Indians initially lived peacefully with the white settlers who had moved into the area of Berks County, Pennsylvania. Things changed, however, when France and England wanted to control the territories west of the Appalachian mountains. Many native tribes aligned with the French and began to attack settlements, which included killing innocent people.

It is easy to look back a few hundred years and point fingers to ancestors who did it wrong. How much better it is to learn from what was wrong and be thankful for what was right Share on X. We ought not let history repeat itself; but too often, it does.

From apple drying to a house fire

I heard the story of the massacre as a child, when family members mentioned it at reunions and in discussions. Ministers used it as sermon leverage to make a point about the wrong of violence. I learned the story well – the part about a father forbidding his sons (excellent marksmen) to shoot at the Indians outside the house in order to spare the family’s lives.

On the evening of September 19, 1757, the young people of the neighborhood came to the Hochstetler farm to help prepare apples for drying. They stayed until late in the evening, and when everyone was gone, the family retired for the night.

In the middle of the night, the dog’s ferocious barking roused the family. Young Jacob opened the door to look outside and fell back, hit by a gunshot in the leg. They managed to bar the door before the Indians could force their way inside. Through the windows, the family was able to see a band of about fifteen Indians. The family had guns and ammunition in the house, but Jacob refused to allow his boys to use them.

Refusing to kill – resulting in the massacre

In spite of Joseph and Christian’s desperate pleas, Jacob refused to allow them to take up arms against another human being even to defend their lives in obedience to God’s command not to kill.1

“We do not kill,” Jacob told his sons. And they didn’t.

Near dawn, the Indians set fire to the house. The family took refuge in the cellar, hoping to escape harm. Next they sprayed cider (stored in the cellar) on the flames, trying to keep the fire at bay. Choking on the thick smoke, they somehow endured the night. At the first light of day and when all was quiet outside, the family decided to climb out the small window in the basement.

There was a young brave, Tom Lyons,2 who lingered in the orchard to gather some of the ripe peaches. He sounded the cry that brought the warriors back. It took longer for Mrs. Hochstetler to get out of the window because she was plump and the opening was small. By that time, the Indians had returned.

Prisoners

The Delaware and Shawnee Indians took Jacob and his son Joseph prisoner. They killed young Jacob and a young daughter (unknown name). It seems the Indians were motivated by a desire for revenge against the mother because they stabbed her through the heart with a butcher knife, a death they considered dishonorable,3 in the presence of her husband and sons.

Christian was about to be tomahawked as well, but according to family stories, he was spared because of his bright blue eyes.4 I remember hearing about those blue eyes.

The Indians allowed Jacob to pull as many peaches off the trees that he could carry. He gave peaches to his sons, in preparation for their journey to wherever the Indians were taking them on foot. This trek ended up being a 17-day journey5 of approximately 430 miles (with a short trip by boat.6

The Hochstetlers had an older son and daughter, John and Barbara, who were both married with small children and lived nearby. Early the morning after the fire, John secretly watched as his father and brothers were led away. With the help of neighbors, they hurriedly buried their mother and siblings when the Indians were gone. I cannot imagine the horror and sorrow they faced for what seemed an unwarranted massacre.

Would they ever see their father and brothers again? Only time would tell.

John and Barbara heard the stories of their father and brothers after their return home years later. Through the descendants of John, Barbara, Joseph and Christian, the stories of the massacre and subsequent years were passed down and are pretty much the same.

The good

The same peach orchard that kept a young Indian brave back and thus caused him to witness the family’s escape and sound the alarm also spared the life of the young boys after they were prisoners of the Indians. When Jacob realized that his sons were in line to run the gauntlet, he took some of the peaches from the orchard to the Chief, who spared the boys from running the gauntlet, possibly sparing their lives.

The peaches Jacob was allowed to take with him provided nourishment and hydration for Jacob and his sons. No doubt they saved his sons lives. The peaches came from the orchard Jacob and his family planted, and God used those peaches and that orchard for good.

The father and sons were allowed to be together for their trek northwest. Each night, he prayed with his sons in their German dialect. He told his boys that, no matter what happened, they should remember their names and continue to recite The Lord’s Prayer daily so they would retain their native language.

Jacob was able to escape and return home less than a year after being taken captive. His sons were adopted by Indian families. After considerable negotiations with Indian tribal leaders to secure the return of all the white captives, Joseph was returned to his father in 1763 or 1764. Christian did not come home until late summer 1765.6

Things I ponder about the why behind the massacre

Mrs. Hochstetler was a plump woman. She cared for her family well. Folklore tells us that once she shooed some Indians away when they wanted to take a quilt that was hanging on her line.

Another time she refused to let them have a pie. I’m sure she had plans for that pie, and it wasn’t for them to enjoy.

The stories told indicate that it was soon after that event that a black X was placed on the door of their house. The house was marked. No one knows for certain why, but Indian authorities tells us that the mark was a sign of what was to come. She was going to pay for her unwillingness to share.

I’ve thought about my 7th great-grandmother Hochstetler since then. Had she understood the culture of these natives, her response would likely have been different. As it was, she viewed these savages through the lenses of her culture instead of theirs. In her culture, a person helps others who help themselves. It is rude to demand items belonging to someone else; but giving items to others is considered generous and benevolent on the part of the giver. She did not understand what interpreting through her culture would do to herself and her family. Nor did the Indians understand that their attempts to take her items could be viewed as theft.

What my 7th great-grandmother did right

My 7th great-grandmother did some things right. This world was new to her; the people (Indians) in her community were foreign to her. Adjustments to a new life, having more children, and working to subdue the land and build a homestead was difficult. Yet she stayed the course.

Her Diligence.

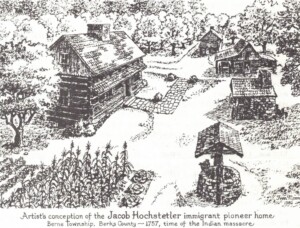

Evidenced by the place they established, she was not one to shirk responsibility and work. By 1739 the family was settled along the Northkill Creek on the eastern edge of the Blue Mountains (now in Berks County, Pennsylvania). They cleared the land, built a log home and farm buildings, and planted several acres of fruit trees. 6 They helped establish the first Amish Mennonite church in America in the Northkill area the following year.7

She worked hard and believed in caring for her family well. She made quilts and clothing for her family, to provide for them. Her quilts and pies are evidence she was not an idle woman.

Her Courage.

She left her homeland in Alsace, France (near Switzerland and Germany) with her husband and two small children. They sailed on the Charming Nancy and arrived in Philadelphia November 9, 1739. John was three years old and Barbara was older. She left her homeland, her family and friends to move to a new county. I have no clue how difficult that would be, and I don’t want to learn, either.

Her Fortitude.

Four more children were born after their arrival in America. During this time, she helped her husband build their house and work the land. She looked out for her family. I smile when I hear how she shooed Indians away from her pies. I also wince. This woman was set to take care of her family. She didn’t want her attempts thwarted, and I can identify. Yet in doing so, she lost sight of hospitality – and I’ve been guilty of the same.

Her Faith.

It is obvious that she supported her husband’s decision to not kill the Indians. She believed God would provide for them – and even though three of them lost their lives, God did provide. Her faith helped instill in her children the belief in God they maintained even in the difficulty they faced following the massacre. In the years following the massacre, John and Barbara lived without knowing if their father and brothers were alive. Their faith, instilled by their parents, helped them live without bitterness for what happened. There was no retaliation. Instead, there was acceptance for what happened, and a determination to continue in their faith, trusting God to bring good out of evil. I claim Barbara as my 6th great-grandmother, and that faith resounds in me today.

What my 7th great-grandmother could have done better

Be neighborly.

As any mother, she wanted to care for her family. Her intent and purpose was to help her husband establish their home and farm, and help in the building of their church. As such, her focus was on her circle of people instead of on the community into which they moved. The Indians were probably not viewed through friendly eyes, and I doubt she made attempts to show hospitality to them or develop friendships with these people so different from her.

Familiarize herself with the local people, including Indians, and their customs.

Her attention was on her family (as well it should have been), but she lost sight of the bigger picture. Perhaps she failed to see her Indian neighbors as folks who needed Jesus as much as she did.

Perhaps their customs and traditions were unknown to her, and learning to know about them was frightening. It’s never comfortable to step outside one’s circle and enter someone else’s, but doing so would have given her a better perspective.

When the Indians asked for her pies, they expected her to give them because their tradition called for someone to give even when they had little to spare. She didn’t understand the damage she did by her refusal. In her thrifty culture, one provided for their own family without expecting handouts. Is it possibly that this colliding of cultures caused her death?

Follow scriptural commands to give.

Every mama who loves her family becomes a mama bear when people tangle with her cubs. Perhaps she was a mama bear when the Indians wanted her quilts and pies. Her family’s needs were paramount, but perhaps she failed to consider scripture’s command to give to those who ask. Might her giving have paved the way for better relationships?

What I know – looking back at the massacre

- Two wrongs don’t make a right. We don’t fix things by returning evil for evil. Retaliation is not a way of peace.

- Bitterness can be passed through generations; so can forgiveness and fortitude. The Hochstetler family did not retaliate or harbor bitterness for the massacre or for being taken captive by the Indians, as evidenced by the stories passed down for generations.

- The faith of my ancestors and their fortitude is what comes through after all these years following the massacre. They could have chosen retaliation or bitterness, but they didn’t. Instead, they chose to trust the hand of God to help them move forward in healing and hope.

- While this story gives me pause, I am grateful that the massacre resulted in physical death only and not spiritual death. My ancestors did not allow this event to annihilate their faith. Therefore their faith, passed down from generation to generation, blesses me.

A postscript -after the massacre

This house is located near my childhood home. I’ve been in it many times. It was moved here to preserve its story and its history. This is the house John Hochstetler (son of Jacob) built and lived in with his family. “Having lost all but two siblings to Indian attacks in 1784, Hochstetler moved his young family to what is now Springs, PA. He was the first white settler in the area, and he was able, through peaceful ways taught by his faith, to make friends with Indians and build his community along side theirs.” 7

Sources

Thanks to Beth Hostetler Mark for her help in getting photos for this post.

FOOTNOTES:

1 http://www.jmhochstetler.com/hochstetler-family.html

2 Ibid.

3 Ibid.

5 https://colonialquills.blogspot.com/2017/01/documenting-hochstetler-massacre.html

6 Ervin R. Stutzman, The Hochstetler Story, 22. Harrisonburg Virginia: Herald Press, 2015), 22.

7http:// www.jmhochstetler.com/hochstetler-family.html

8 http://spruceforest.org/little-house.php

BIBLIOGRAPHY:

https://colonialquills.blogspot.com/2017/01/documenting-hochstetler-massacre.html

http://spruceforest.org/little-house.php

http://www.jmhochstetler.com/hochstetler-family.html

Stutzman, Ervin. R., The Hochstetler Story, (Herald Press, Harrisonburg, Virginia) 2015.

Interesting story and thoughts!

Do you know where the Slabach family comes from?

My husband’s ancestors came from Germany and Switzerland, as did mine. The original spelling was Schlabach.

This is interesting! In the German region of Siegen where I originally come from there are several people named Schlabach.

When I was a little girl a mennonite woman, Grace Stutzman, sometimes came to the Siegen area where she met German relatives (our neighbors) and as far as I remember she told us that their ancestors’ name was Schlabach.

Interesting. My husband’s family’s name is originally spelled Schlabach. His grandfather changed it to “Slabach” because there were so many with his first and last name that it was difficult for people to keep his business apart from others; so he took the “ch” out of the name.

The first time I heard this story was in the children’s book Test of Faith by Vera Overholt. Such a sad story indeed. I appreciate Jacob’s faith to not kill the Indians even though doing so might have saved more lives.

Thank you for sharing this story.

You’re welcome! I have yet to get that children’s book – but it’s on my list of things to do!