Finding My Great-Grandpa’s Grave

“This is a broken world, and we are broken people.”

What do you do about a dark thread in your family’s past? How do you handle the grief of years past? Is there hope and healing for those who suffer such loss?

A guest post by Dorcas Smucker, who blogs at Life in the Shoe . Dorcas has a column “Letter from Harrisburg” in The Register-Guard.

Finding My Great-Grandpa’s Grave

The last few years, I’ve been intrigued with family stories, and this sad tale of my great-grandpa in particular. Here’s the brief version:

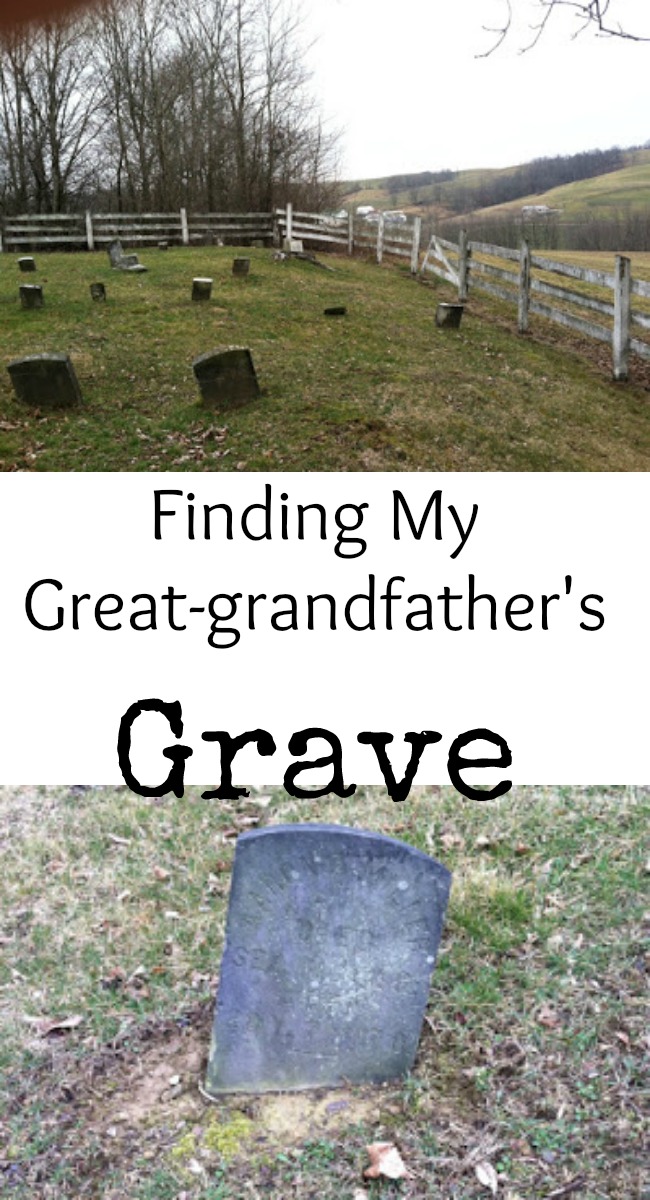

Aaron Miller was a fine young man living near Charm in Holmes County, Ohio. At 28 years old, he was married to Mary and had two little boys, Enos and Adam. Mary was pregnant with a third boy. Aaron was known to be a capable and hardworking farmer.No doubt all these things factored into the church ordaining him to the ministry in the spring of that year. Unfortunately, the church was having serious problems.One day, at about noon, Aaron told his brother he’s going out to see if the clover was ready to harvest. The afternoon wore on and he didn’t return, so the family went looking for him.He had taken his own life, hanging himself in a tree.Such a death carried such terrible shame in the Amish culture that he was buried outside the cemetery, on the other side of the fence.We heard the story from Mom, never in a lot of detail, but at least it was honestly told. I thought about it a lot more after I lost a nephew, Leonard, to suicide almost ten years ago.What are these dark threads weaving through our lineage, I wondered, wreaking such unspeakable pain? Was there hope for our children? Did our story go on? Were we doomed to terrible secrets and continual shame?The reason for our trip to Ohio last month was to speak at a women’s retreat. But what a great opportunity to take a side trip into our family history.A few years ago, I heard a hint that maybe the fence had been moved to include Aaron’s grave inside the cemetery. Strange how that news gave me a lift of hope, for myself now, for the future, and even back into the past. I was determined to find his grave and see for myself.I emailed my brother Marcus who contacted our second cousin Marvin for directions, and in the morning, before the retreat started that afternoon, we followed the directions out of Berlin and down ever-narrower back roads until we were back in the hills creeping along a one-lane dirt road, looking for a lane to the north.Finally we asked an Amish girl on a bike, and she pointed us to the lane we had passed twice. “Follow it on back,” she said, “Past the house.”So we did. It went from gravel to mud to a grassy track, and there on a bit of a rise was the little cemetery, beautiful and old and quiet and looking out over a valley with fields and a sawmill.We opened the gate and went in, and within minutes we found it, a small, tilted gravestone for Aaron Miller.Suddenly I was in tears, thinking of that terrible terrible day, the horse-drawn hearse slowly trundling back that long lane, the long line of silent people, that desolate little widow, 25 years old, rounded with child, holding the hands of two frightened little boys, and the overwhelming sense of disaster, of darkness, of abandonment, of condemnation, of loss.Then, in a final twist of pain, her young husband that she loved and desperately needed was buried outside the fence, because his deed was too bad to ever be atoned for, and the whole community saw her and her boys as the tainted leftovers of his sinful choice.So I cried for her, and for all of us since who have lived under any cloud of shame and rejection, and did not know that there are words for this, and truth, and hope, and help, and even, impossibly, redemption.I don’t know how or why the decision was made, but at some point in the fairly-recent past, the cemetery needed to be enlarged, and they moved the fence so that it now encloses Aaron’s grave, and he is now buried with his community and his people.

At the far end, on the right, you can see where the new part of the fence begins. I wished I could tell my great-grandma about it.Later that day, I found a genealogy book about my ancestors in the Anabaptist Heritage Center. Several pages were devoted to Aaron’s death. An old account reads, “The deceased . . . left a wife and 2 children, father, mother, brothers, and sisters, who are deeply sorrowing over this rash deplorable act.”This is a broken world, and we are broken people. Depression is genetic and really awful, and sometimes it overpowers a person and wins.But it isn’t the end of the story. I am sure of that. Here we are, Aaron’s descendants, and there are lots of us, and we are survivors and storytellers and moms and dads and students and singers, and we get to see sunsets, and we fight hard.We still grieve for Leonard, but we know that Jesus takes away not only guilt but also shame, and He heals. We have moved on, and we have redeemed his death by talking about depression in honest words, by asking for help, and by a deep and continuing compassion for hurting people. We are not ok with “fine” when we ask “How are you?” We are adamant about wanting the truth.We believe that the story goes on.

I wish I could go back and tell my great-grandparents that the word is depression, it isn’t their fault, there are things you can do for it, and it’s ok to ask for help. I’d like to tell them that the shame their community placed on them was not from God, and that Jesus takes our shame and gives back His glory. I want to tell them that silence is wrong and unnecessary, the truth will set them free, and they are unimaginably loved. And they have a hope and a future.

Since I can’t tell them, I am telling you instead.